Ai Weiwei: ‘It is so positive to be poor as a child. You understand how vulnerable our humanity can be’

From living in a dugout in Little Siberia to his friendship with Allen Ginsberg in New York, artist and activist Ai Weiwei reveals what drives his restless creativity

Ai Weiwei is hard to pin down. For the first few minutes of our Zoom call, him bleary-eyed at his computer, I think he’s talking to me from his new base in Portugal. My mistake – it’s Vienna, where he’s planning a show for next March. A year and a half ago, Ai was giving interviews about his new life in Britain; before that it was Germany, the country that offered him safe harbour when he finally left China in 2015, after years of hounding by the authorities and a spell in detention. So where does he actually live?

“Yeah, the question always comes up,” he says sheepishly. He moved to Cambridge so his son, Ai Lao, could improve his English. His son is still there, but in the meantime, “I found a piece of land near Lisbon, so I’m kind of settled there, but that’s only for the past year”.

A star of the Chinese art scene from the mid-90s on, Ai became a household name in the west after he helped conceive the “bird’s nest” stadium in Beijing for the 2008 Olympic Games, before rejecting its use as “culture for the purpose of propaganda” and refusing to attend the opening ceremony. His many projects since have continued to needle the Chinese state, up to and including Coronation, his 2020 documentary about the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan.

You’d expect an artist as globally famous as him to do a lot of international travel, of course. But there’s something more to his un-rootedness. He explains, a little gnomically: “Once you don’t have a place to go, you can go anywhere.”

You mean, once you’ve left your homeland, you can make a home wherever you like? The word doesn’t sit well with him. “I’m still a Chinese citizen, a passport holder. But I don’t feel that it is my homeland. I speak Chinese and I’m a typical Chinese – but I never had a home there. The year I was born, my father was exiled. So my story started with no home, just being pushed away to a very remote area as some kind of enemy of the state.”

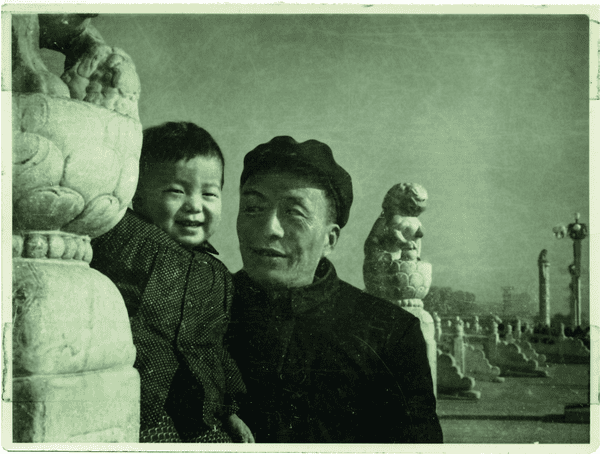

It’s true that Ai’s trajectory is impossible to understand without knowing about his late father, Ai Qing. Regarded as one of China’s greatest poets, Ai Qing was a leftwing hero, having been imprisoned in 1932 for his links to communism. Later, he was a friend and an intellectual sparring partner of the Communist party leader Mao Zedong, before dramatically falling from grace in a purge of so-called “rightist” intellectuals. This story is told in painstaking but often beautiful detail in Ai’s new autobiography, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows. It’s more like a dual biography, with Ai Qing’s story taking up the first 150 pages, a useful corrective for westerners who know little about him.

What jumps out from those passages is the sheer cruelty of Mao’s system of ideological enforcement, and the abject conditions Ai experienced as a child. The bleakest period was when Ai Qing and his two sons lived in a dugout in “Little Siberia”, part of China’s far north-west. Their “bed” was a raised dirt platform covered with wheat stalks, with a square hole in the roof to let in light. The paraffin lamp they used inside made their nostrils black with soot. Rats were a constant problem, as were lice. Ai Qing’s job for much of this time was cleaning out communal toilets, which consisted of holes over a cesspit. In winter, this involved “breaking up the frozen faeces into manageable pieces and shifting them out of the latrine one by one”. Eventually, his father was rehabilitated, and the family moved to Beijing.

When I ask Ai about this period he picks up his phone and turns it to face the camera. His homescreen is a black-and-white photograph of the dugout, a reminder of how difficult life can be – or at least that’s what I assume. “Well, it was a hard time, but you have a lot of joy, too.” How so? “You feel safe. You’re under there, you’re at a different level from other people. They’re all above you, but you feel safe.” He goes further: “I think it is so positive, to be poor, and to have an empty life as a child. I think you establish an understanding of how vulnerable our humanity can be.”

Ai is given to bold statements like this that don’t necessarily stack up. The experience of grinding poverty may be useful to look back on, but perhaps only when cushioned by wealth. I’m not sure he always thinks through the implications of what he says, but I’m not sure he cares all that much either. Perhaps this is the legacy of his childhood: when you’ve already been rejected in the most extreme way, there’s little to fear from people’s opinions of you. But it also seems to have engendered a kind of nihilism.

I ask what motivates him. “Good question,” he answers. “You know, without your interview, I wouldn’t know what to do today. I have so many shows, but I never initiated a show and never contacted a curator in my lifetime.” If it wasn’t for people getting in touch, he says, “I might be wandering on the beach, trying to find some beautiful shells.”

It’s an extraordinary comment for someone as prolific as Ai. Each year he produces several major solo exhibitions (in 2016 he had 17, from California to New York to Turin to Athens). His work takes in photography, sculpture, film and social experiments such as Fairytale, in which he arranged for 1,001 Chinese travellers to visit the German town of Kassel. At other points he has strayed into something resembling journalism, attempting to document the names of children killed in the Sichuan earthquake when the authorities failed to record them. He is assisted by a small army of helpers: he says their number varies, but “if we do large projects it would be hundreds, sometimes thousands”.

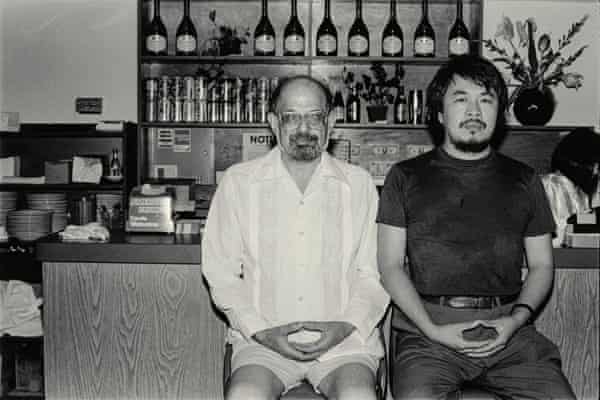

As a child, he says, he had no dreams for his future, because such things ran counter to communist ideology. Ambition was a dirty word: “If the doors and windows are shut, you don’t have a view.” But even after he escaped to New York in his early 20s, he drifted, enrolling at Parsons School of Design but flunking his final exams by simply writing his name at the top and nothing else. He rented an apartment on the Lower East Side, worked night shifts at a print shop, and lived the life of a flâneur. At St Mark’s Church one evening, he listened to Allen Ginsberg recite a poem about China; it contained a line about “revolutionary poets [sent] to shovel shit in Xinjiang”. Ai approached him, explained the connection, and the two became friends. He remembers him as “a wonderful man, very kind, but with the heart of a rebel”.

His wanderings also took him to the Strand Bookstore on Broadway, where one day he picked up The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, a book of the artist’s deadpan observations on fame, love and work. It obsessed him. He singles out Warhol as one of the key influences on his life, alongside the conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp, his father and, more surprisingly, the philosopher Wittgenstein.

“I was so fascinated by this individual who seemed so empty, but at the same time was a true reflection of our American culture,” he says of Warhol. He is disappointed that they never met, though he attended a couple of gallery openings in the great man’s presence. “Warhol understood irony so well, but also tells the truth. Very harsh truth in his writing. He was 50 years ahead of his time. He understood free expression, media and communication, he was taking selfies all the time, recording people all the time.” Does he feel they have a lot in common as artists? “We are both sincere and insincere at the same time. And we love life, but without goals, without purpose.”

I point out that Ginsberg and Warhol – and Wittgenstein for that matter – were gay. “Gay people in society have a complicated state of mind … they are generally more sensitive and smarter,” Ai says. This is another one of those disarmingly bald statements that someone more anxious about how their words are received would avoid. I find myself trying to reshape it for him: is it that they have a more complicated relationship with society? “They are complicated, and that complication gives them insecurity, because they’re different. And that insecurity makes them, you know, more sensitive – they are artists, poets, musicians.” I find this an amusingly pat description of the gay condition, but I’ll take it.

Back to Warhol: what would he have made of the internet? Would he have enjoyed memes and social media? Ai thinks no, he probably wouldn’t – what he liked about selfies and live streams (as you could credibly call some of his eight-hour movies) was that he was the only one doing it. Ai, on the other hand, is famous for his love of Twitter, seeing it as a tool for free expression and connection. And while you imagine Warhol would have revelled in our current state of advanced capitalism, for Ai there is no bigger threat to humanity.

“I used to think the danger was from authoritarianism. But now, I really sense that corporate capitalism is a bigger danger to the whole human environment. It’s going to totally destroy human society by encouraging the desire just to have more, just to get profit.” Does that mean he’s come full circle to communism? “I don’t think so. I hate the communist viewpoint. I think that only belongs to the past.” So what is his solution? “We have to go back to humanism.” What does that mean, though? “Respect for individuals’ lives, property and development,” he says, throwing me slightly by mentioning property, which suggests at least some sympathy with capitalism. Humanism centres “individuals rights to be themselves and speak out about what they’re thinking”.

If other aspects of his political thinking are confused, there’s no mistaking Ai’s commitment to free speech. Donald Trump may indeed pose a danger to democracy, he says, but the “much bigger danger” are social media platforms that “manipulate our thinking” by banning him. The freedom to say it as he sees it is perhaps the only real guiding principle of Ai’s eclectic career, and provides another link back to his father, who wrote Mao a long letter about the need to preserve artists’ ability to speak the truth, whatever the circumstances.

Ai tells me he has “no plan, no goal, no purpose of my life”. But that’s not quite right. His plan is to be himself, unfiltered. It’s a quest that explains his restlessness and dizzying productivity, which, even during the pandemic, gave rise to more shows, more public art, 10,000 printed face masks, the Wuhan film and, of course, the book. I ask him what he thinks the job of an artist is. “The job of an artist is to have no job,” he laughs. What matters is to “stay alert” and “speak out with truth”. Ai Qing would no doubt agree.

1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows by Ai Weiwei, translated by Allan H Barr, is published on 2 November by The Bodley Head.

Comments

Post a Comment

Your opinion counts